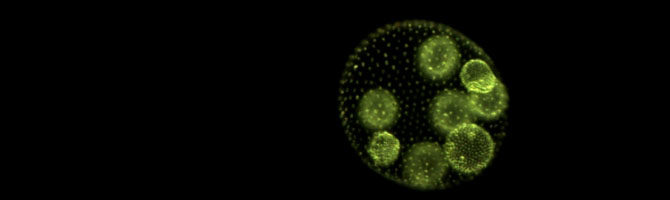

The paper describing the genetics of the multicellular Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain that evolved in response to selection on settling rate is published in Royal Society Open Science:

The paper describing the genetics of the multicellular Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain that evolved in response to selection on settling rate is published in Royal Society Open Science:

I’m a junior author on a new paper from Erik Hanschen and colleagues, “Multicellularity drives the evolution of sexual traits.”

A news item by Elizabeth Pennisi in Science mentions our work experimentally evolving multicellularity in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii:

[Will Ratcliff’s snowflake] yeast results weren’t a fluke. In 2014, Ratcliff and his colleagues applied the same kind of selection for larger cells to Chlamydomonas, the single-celled alga, and again saw colonies quickly emerge. To address criticism that his artificial selection technique was too contrived, he and Herron then repeated the Chlamydomonas experiment with a more natural selective pressure: a population of paramecia that eat Chlamydomonas—and tend to pick off the smaller cells. Again a kind of multicellularity was quick to appear: Within 750 generations—about a year—two of five experimental populations had started to form and reproduce as groups, the team wrote on 12 January in a preprint on bioRxiv.